There’s a figure on the edges of the Mitford family saga who has received little attention. The six famous sisters had, albeit briefly, a German-Jewish aunt. She was rarely spoken of, and while Nancy might have found the connection intriguing, it would have been anathema to Unity or Diana. This was Marie-Anne, also known as Marianne, who married into the family in 1914, and just as swiftly exited from it. The story of her marriage to Uncle Jack and of the different paths the couple took after their parting is worth the telling.

Marie-Anne von Friedländer-Fuld (b. 1892) was the only child of the Berlin ‘Coal King’, Privy Councillor Friedrich von Friedländer-Fuld. Her father, a self-made industrialist who dominated the Berlin coal market, was reckoned by the New York Times to be worth in excess of $11 million, and steward of an even larger fortune his daughter stood to inherit. Friedrich, it was reported, was among the men on whom the Kaiser depended financially for his ‘patriotic schemes’. Although Marianne’s ancestry on both the father’s and mother’s side was Jewish, the family had converted to Christianity and was ennobled by the Kaiser in 1906. The family’s palatial home on the Pariser Platz near the Brandenburg Gate was a social hub, and the young heiress did not lack for suitors. Newspapers trilled that she was a ‘beautiful brunette’, an accomplished linguist and a fearless horsewoman, whose earlier engagement to a cousin of the Tsar had been thwarted only when Nicholas II learned of her Jewish parentage. Known to her friends as ‘Baby’, she was also a discerning art collector, with an eye for Impressionists and other modern masters. By 1914 she had already acquired at least one valuable asset in a Van Gogh portrait, ‘L’Arlésienne’ (of which more later).

The Hon. John Mitford (b. 1885), known as ‘Jack’ or ‘Jicksy’ within the family, was cut from rather different cloth. Reportedly the favourite among his father’s five sons, he is described in The House of Mitford as a ‘charming scapegrace’ and a ‘rolling stone’ who was ‘well known in the family for being a card’. Expelled from Eton, he’d been unable to enter the diplomatic service for which his father had destined him. He instead chose banking as a career, moving to France in 1907, ostensibly to learn Continental business practices, then to Germany. From 1910 to 1913 he was engaged in private banking for Warburg in Hamburg. He met Marianne at the Kiel Regatta – probably introduced by their mutual friend, Admiral Prince Henry of Prussia, the Kaiser’s younger brother and Patron of the Kiel Yacht Club – and proposed. According to David Pryce-Jones, whose grandfather attended the wedding, the marriage was Prince Henry’s idea: a misfiring attempt at Anglo-German alliance. In addition to gifting the couple a luxurious house in the Bendlerstrasse, as part of the marriage settlement Friedrich von Friedländer-Fuld made his new English son-in-law a partner in the family business – unkind souls suggested in order to ensure the accumulated wealth was likely to remain in Germany. It was reportedly a condition of the marriage contract that the couple were not to reside entirely in England. Whatever expectations the contracting parties brought to the table, the wedding was bound to be the highlight of the Berlin social calendar in early 1914.

Celebrations began with the ‘Polterabend’, the traditional eve-of-wedding ball, on 4 January, a spectacular affair. In a room which was an exact replica of Frederick the Great’s Concert Room at Sans Souci, a company of 300 sat down to dinner. Once the tables had been cleared, aristocratic eyebrows were raised when the tango was danced, the Kaiser having decreed that the tango was strictly forbidden at houses frequented by Army officers or members of Court society. Music was provided by the ‘Philharmonic Orchestra’ (presumably the Berlin Philharmonic?) and the evening ended with live drama. Max Reinhardt brought members of his Deutsches Theater troupe to act scenes from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with Gertrud Eysoldt as Puck and Alexander Moissi as Oberon, and there was an exhibition dance by Grete Wiesenthal, one of the leading exponents of ‘modern dance’ in Germany at the time.

After a civil ceremony the following day, the service at Trinity Church on 6 January 1914 followed Lutheran rites. Guests numbered ambassadors, Prussian ministers, military brasshats (including Moltke, Chief of the General Staff) and the most prominent Berlin families – though, not it seems, any members of the Imperial Family, who pleaded a prior engagement. The wedding broke with German precedent, for it had hitherto been custom at society weddings to wear evening dress, however early in the day. In deference to the bridegroom’s nationality, the dress code was ‘English’, i.e. morning dress. The bride was in white satin, with a veil of old Silesian lace. In his address, the pastor noted the coincidence that this union of Redesdale and Friedländer-Fuld families was forged ‘at a time when Anglo-German political friendship was increasing’ and urged the young couple to fill their house ‘not only with material things but with the Anglo-German spirit’. It was a spirit that would not survive the year, on either the personal or the international level.

What happened next is a matter of conjecture, not least since both families made efforts to hush the matter up. When the honeymooners returned from six weeks on the Riviera, something was awry. Although Lady Redesdale was able to present her new daughter-in-law to King George and Queen Mary at Court on 13 March (Marianne wearing her much-admired wedding dress), within another month it was known that ‘Baby’ had decided to live apart from her husband. Jack returned to England, Baby to her parents’ home, and the house prepared for the couple on the Bendlerstrasse was left temporarily unoccupied. Rumours circulated in Berlin that the cause of separation was ‘unnatural conduct on the part of Mr Mitford’. This gossip was picked up by The Sporting Times in London and ill-advisedly repeated in an article in July. The paper didn’t refer to the Mitfords by name, but only by inference after linking their story to that of another married couple. Still, this was enough for Jack to launch a libel action against the paper. In an affidavit he attested that he had lived an ‘absolutely clean life’ and there was ‘not an atom of truth in the abominable suggestion’ in the article. In his eyes, the couple were ‘perfectly happy’. His wife, he said, had become ill in May and entered a sanatorium. On his second visit to her there, she had informed him they were ‘unsuited’. He couldn’t account for her ‘strange and sudden determination’ but believed it to be only temporary. As evidence that she was still ‘full of affection’ for him, he produced a letter she’d written to his mother, Lady Redesdale. The tone is certainly conciliatory – but perhaps disingenuous, given the legal action she was contemplating in Germany to end the marriage. She apologises for ‘the pain I am giving your beloved son’ and assures her mother-in-law that Jack ‘never wronged anyone’; nevertheless, since the couple ‘lived away from one another inwardly’, she insisted there had to be a parting of the ways.

For some reason, Jack had gone down a precarious legal route. Under English law at the time, prosecutions by private individuals could be begun by ‘criminal information’ as well as by indictment. However, individuals had to obtain the leave of the court to file an information. A case in 1884 had already decided that that there would be a presumption against granting this right to private individuals as distinct from someone in public office. (Indeed, ‘criminal informations’ were abolished in 1938.) In Jack’s case, the Lord Chief Justice opined that while the paragraph complained of undoubtedly contained ‘matter of a grave character’, he didn’t consider it grounds for a criminal information, given that Jack was not a holder of public office.

Thus he had only succeeded In drawing his marital problems into the public arena. Baby remained fixed in her determination to end the marriage and in June 1914 petitioned the German court on the grounds that Jack was ‘addicted to masculine indolence and unbearable selfishness’. She successfully invoked a curious provision in the German Civil Code which allowed a spouse to dispute the validity of a marriage if either party was ‘mistaken as to the personal attributes of the other spouse’ at the time of the marriage. The court, finding in her favour, declared the marriage null and void in October 1914. Jack was not best pleased. He instructed his lawyers in Germany to refute the charges against him. However, after the outbreak of war in August, he couldn’t communicate with them directly and was unable to give evidence in person. His counsel appealed twice on his behalf in 1916 – ultimately to the Imperial Supreme Court – but the higher courts upheld the original decision.

We know all this from reports of another court case initiated by Jack in the English courts, which seems to have been as ill-starred as his earlier libel action. Marianne had remarried in 1920, to the diplomat Richard von Kühlmann. In March 1921, Jack, who still regarded her as his lawful wife, petitioned the High Court in London for dissolution of his marriage on the grounds of Baby’s alleged bigamy and adultery with Kühlmann. The English court found – predictably, one would have thought – that since the dissolution of the first marriage and the contracting of Marianne’s second took place in Germany under German law, the English court had no jurisdiction. The ground of ‘mistaken identity’, though it would be immaterial in English law, was valid under German.

But this is jumping ahead. To revert to the events of autumn 1914… At the outbreak of war Jack did not wait to be conscripted but immediately joined the Life Guards, to serve with the British Expeditionary Force in France. The empty marital home in Berlin was used at first to house East Prussian refugees before welcoming a more illustrious resident at year’s end. Marianne had met the poet Rainer Maria Rilke at a funeral in November. An invitation to tea followed and Rilke was soon a regular visitor at her parents’ home to which she had now retreated. Hearing that Rilke was in need of accommodation, she offered him rooms in the half-vacant Bendlerstrasse house. He moved in before Christmas. ‘She is a marvellously beautiful creature,’ he wrote later, ‘who, emerging from childhood of which she still bears the dark traces, had suddenly been transformed by a touch of fate into an independent limpid personality, transparent through and through.’ She became one of his closest confidantes and throughout the war, when far from Berlin, Rilke honoured her with lengthy letters drawing on their shared passion for art in which, as his biographer puts it, a ‘faint hint of the erotic was always overlaid by his didacticism and self-preoccupation.’

The death of Marianne’s father in July 1917 left her a very rich woman. In 1922 she became a limited partner in the family firm, a position she held until 1936 when Nazi race laws forced the exclusion of Jewish staff and the confiscation of family assets. The marriage to Kühlmann which so exercised Jack’s litigious instincts was short-lived. After the birth of a daughter, Antoinette, they divorced in 1923. She then married the painter Rudolf von Goldschmidt-Rothschild. Marrying this time into an observant family, she returned to Judaism. A son, Gilbert, was born in 1925. As a refined Berlin salonnière she flits across the pages of diarists in the 1920s. The artistic patron Count Harry Kessler was one such. He records her taste for amateur dramatics (at one soirée she improvises a parody of a play by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, causing Kessler, one of Hofmannsthal’s closest friends, to see the hollowness of a work he once revered). He visits her one afternoon in 1926: ‘She received me in bed, between pink damask sheets and in blue pyjamas, the Chinese bed upholstered in yellow satin. A setting appropriate to the bedroom scene in a play about adultery.’ Three years later, after she hosts an intimate dinner party, thirty Van Gogh letters in an ‘excessively ornate, ugly binding’ are handed round with cigarettes and coffee. Kessler starts to fret that acquisitiveness may have got the better of connoisseurship. ‘Poor Van Gogh!’ he muses to his diary, disgusted at the ‘falsification and degradation of intellectual and artistic values to mere baubles, “luxurious” possessions.’

Entering the 1930s, she was increasingly exercised by the plight of German Jewry. It was said that, after the passing of the Nuremberg Laws, she took (in defiance?) to wearing a Star of David of yellow diamonds. In September 1936 Winston Churchill, returning from one of his painting holidays on the Côte d’Azur, dined with her in in Toulon and heard early hints of an unfolding horror in Europe. He wrote to his wife Clementine that Marianne was a remarkable woman who had told him ‘terrible’ tales of the treatment of Jews in Germany.

Like the two before it, the marriage to Goldschmidt-Rothschild did not last, and Marianne was once more a divorcee when she fled Germany in October 1938. She emigrated first to France, before making her way in 1940, via Spain, Portugal and Mexico, to the USA, where she sat out the remainder of the war. Accompanying her were the two children from two marriages and some of the precious artworks, including the Van Gogh. On returning to Europe in the late ‘40s, she sought restitution of property and assets, with partial success. She published her letters from Rilke (in French translation) in 1956 under the pseudonym ‘Marianne Gilbert’. As for ‘L’Arlésienne’, she vowed that when Paris was liberated she would donate the canvas to the French nation: following her death in 1973 it hangs now in the Musée d’Orsay.

Jack, for his part, never remarried. After his failed law suit in the early ‘20s, he seems to have accepted that Baby was lost to him. Pryce-Jones describes him in later life as ‘a somewhat Ivor-Novello-model of a bobbish man about town’ and ‘the inspiration behind the International Sportsman’s Club in Grosvenor House.’ He was secretary of the Marlborough Club and a regular visitor and competitor at St Moritz for the Cresta Run, where he was pictured with various photogenic young women, including Sheilah Graham, the upwardly mobile Englishwoman who would go on to have an affair with Scott Fitzgerald. A photo spread in the Tatler in 1933 captures Unity and Deborah Mitford on the ski slopes watching their ‘adored Uncle Jack’ compete in the Curzon Cup. He made headlines briefly in February 1940 after Unity had been invalided out of Germany following her suicide attempt, telling reporters he ‘did not credit the theory’ that his niece’s bullet wound was self-inflicted. Thus are conspiracy theories born. (Several months after this George Orwell records in his diary a rumour that Unity was pregnant by the Führer – another canard that continues to resurface to this day.) In his final years Jack was looked after by his unmarried sister Iris. He inherited the baronetcy from his childless older brother Bertram in 1962, to become the fourth Baron Redesdale, but died only a year later; as Jack was also without issue, the title passed to his nephew Clement.

Perhaps it was all there in the wedding photo. A slightly Bertie-Woosterish bridegroom inclines towards a serene bride, her gaze fixed straight ahead. An elderly lady (the bride’s mother?) looks on sceptically, wondering if it will last. An affable, sporty English gentleman, none too bright, whose pleasures were skiing and sailing, weds a cultured German socialite with a compensating social conscience, at ease among poets and artists. Add in the fissures of nationality and race that ran through their troubled era. The outlook was never good for this particular Anglo-German alliance.

[Principal sources: The Times Law Reports; New York Times; Jonathan and Catherine Guinness, The House of Mitford: Portrait of a Family (1984); David Pryce-Jones, Unity Mitford: A Quest (1976); Donald Prater, A Ringing Glass: The Life of Rainer Maria Rilke (1986); Count Harry Kessler, The Diaries of a Cosmopolitan, 1918-1937 (1971); Marianne Gilbert, Le tiroir entr’ouvert (1956).]

Philip Ward is a writer and translator with particular interests in literature, music and drama. He blogs at www.brushondrum.blogspot.com.

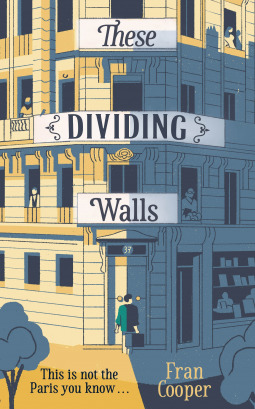

These Dividing Walls by Fran Cooper

These Dividing Walls by Fran Cooper

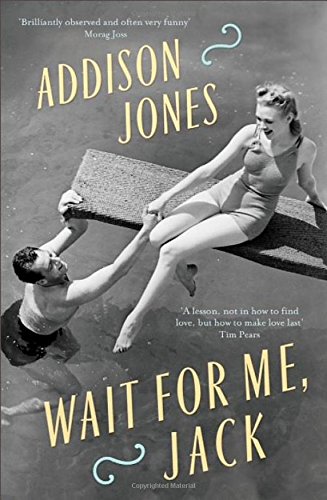

Beginning in the early 2000s and working backwards to 1950, this is a story of a marriage told in reverse. Milly and Jack meet in San Francisco at the age of 21; he is a war hero, and she a secretary. When she marries and has children, Milly begins to feel as though her identity has been stolen. Jack is working in a job he hates and is frustrated at how his life is panning out. And so the conflict begins, and escalates as the years go on. As they examine their lives, they realise they have simply settled for less – she fights her inner thoughts about her children and how they do not fulfil her, and he feels short- changed by the American Dream. But the experiences they have shared over 60 years ultimately bind them together. Told from both of their perspectives, with a dash of black humour, it is an insightful book that reveals home truths about love. A compulsive read.

Beginning in the early 2000s and working backwards to 1950, this is a story of a marriage told in reverse. Milly and Jack meet in San Francisco at the age of 21; he is a war hero, and she a secretary. When she marries and has children, Milly begins to feel as though her identity has been stolen. Jack is working in a job he hates and is frustrated at how his life is panning out. And so the conflict begins, and escalates as the years go on. As they examine their lives, they realise they have simply settled for less – she fights her inner thoughts about her children and how they do not fulfil her, and he feels short- changed by the American Dream. But the experiences they have shared over 60 years ultimately bind them together. Told from both of their perspectives, with a dash of black humour, it is an insightful book that reveals home truths about love. A compulsive read.

The House of Birds by Morgan McCarthy

The House of Birds by Morgan McCarthy

Too Marvellous for Words by Julie Welch

Too Marvellous for Words by Julie Welch The Secret Orchard of Roger Ackerley (Slightly Foxed reprint edition) by Diana Petre

The Secret Orchard of Roger Ackerley (Slightly Foxed reprint edition) by Diana Petre In The Great Green Room: The Brilliant and Bold Life of Margaret Wise Brown by Amy Gary

In The Great Green Room: The Brilliant and Bold Life of Margaret Wise Brown by Amy Gary Joan: The Remarkable Life of Joan Leigh Fermor by Simon Fenwick

Joan: The Remarkable Life of Joan Leigh Fermor by Simon Fenwick The Book of Forgotten Authors by Christopher Fowler

The Book of Forgotten Authors by Christopher Fowler